If you’ve got a gas grill, you can still turn out some truly amazing, authentic BBQ. Here’s how.

I know there are those people out there who are going to hate this post. Trust me, I understand. But ultimately, I’m about results – And if the technique yields sound results, then it’s a sound technique. I have a BBQ smoker, and I love it – but most of the time I don’t have 12 or 15 hours to sit around and fiddle with a fire, and I if I can bring a 12 hour cook down to a 5 hour cook and turn out some BBQ that’s nearly indistinguishable from what I produce on my smoker, I’m down. Also, many people may not have room for two or three cookers in their back yard (like I do). This post is dedicated to BBQ lovers who want more of that smoke-kissed flavor in their lives.

In this post, we’ll be exploring two things: First, how to use your gas grill as a smoker – and some of the sciencey stuff that goes on behind the scenes when using smoke. Second, we’ll talk briefly about what types of wood to use and how.

Things You’ll Need

Grill

Smoker Box and/or Cast Iron Skillet

Wood Chunks

Stand Alone Oven Thermometer

Decent Instant-Read Thermometer

Meat

BBQ Rub (try Classic BBQ Rub, if you like).

The Key

Basically, the key to this whole thing is this: You’ve got to learn to think of your grill as an oven. That’s it. Most of the time, we think of our grills as… grills. In other words, we sear food (burgers, steaks, whatever) directly over high heat until it’s done. We’re using primarily conduction and some convection to get heat into the food. When you roast or bake something, you’re using a little bit of convection and mostly radiation. In other words, it’s heat in the form of waves penetrating your food.

Smoking is simply baking and/or roasting something in the presence of smoke.

I remember one Thanksgiving, the oven caught fire. Faced with trying to figure out how to cook a 15lb turkey with no oven, I turned to my grill. I lit one burner and plonked the bird down on the cool side of the grill and everything turned out fine, albeit a little dry. That’s where the lightbulb went on. Since then, I’ve developed a technique that I think is pretty damn solid.

The Technique

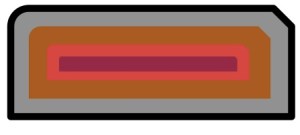

They say a picture is worth a thousand words, and Bon Appetit has a great picture to explain this, so I’m just going to use theirs:

A: Single Burner Lit, B: Pan for catching drippings, C: Smoker Box, D: Smoke, E: Meat

All that being said, there’s a few modifications I’d make to the picture above:

- Remove all but one of your grill grates so you can slide the food from hot to cold without picking it up, if need be.

- Place the smoker box directly on the flavorizer bar (as in the cover photo for this post), NOT on the grill grate. Basically, I’ve never been able to get anything to smoke on the grill grate – not enough conductive heat.

- Leave the lid off the smoker box, or simply use a small cast iron pan.

- Use wood chunks instead of chips. Chips burn up way too fast, whereas chunks will smolder for an hour or more. The only time I use chips is as a starting agent; i.e., place some chips down on the smoker box with a few chunks on top just to accelerate the process a bit.

- Don’t bother to soak your wood chunks (or chips) ahead of time. This does nothing, other than make it take longer for them to start smoking. I’ve timed, by weight, how long it takes wood chunks soaked for 24 hours, 1 hour, and not at all, from the time they start smoking to the time they burn up, and it’s the same. What’s not the same is the amount of time it takes for them to start smoking. Soaking wood chunks just extends your pre-heating phase. Trust me, don’t waste your time.

- Do keep a trigger spray bottle handy. Sometimes when you open the lid (which you shouldn’t do too often) a lot of oxygen will very suddenly make its way to the wood chunks and they will burst into flame. No need to soak them – just a couple squirts to calm them down again and shut the lid… continue on your merry way.

- Invest in a $5 stand-alone oven thermometer to place on the grill grates. Chances are the thermometer built into the hood of your grill (if you have one) reading as much as 50F different than the actual temperature at grate-level.

- Shoot for 275F at grate level. Actually, anywhere between 275F and 300F is fine. 275F is my go-to temperature for smoking just about anything, even if I’m using a traditional smoker. Many people will say that’s high, but it’s basically been proven that the only difference between 225F and 275F is the amount of time it takes to get something up to temperature (duh), but might mean more time in the presence of smoke. However, competition BBQ teams these days are sometimes smoking brisket at north of 300F. The reason? Once something has been basking in smoke for more than three hours, any appreciable difference thereafter begins to fade in a damned hurry.

- Put about an inch or so of water into the drip pan beneath the meat. This will eliminate the possibility of any flare ups from rendered fat, and keep everything underneath the hood nice and moist.

How to Smoke Stuff: Cooking Times and Temps

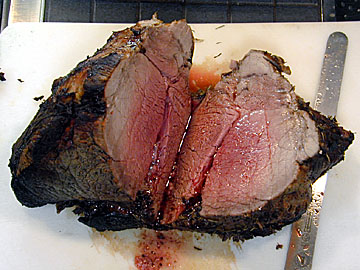

These are fairly rough – but predictable – cooking times for various meats I’ve done using this technique. Make sure to generously season your meat with a good BBQ Rub so that there’s something for the smoke to stick to.

I always use a two-step process. During the first phase (three to four hours) you get smoke onto the meat. During the second phase, you finish getting the meat up to temp (190F – 205F) by wrapping it in foil. It’s such a common practice that it actually has a name – the Texas Crutch. I won’t go into a lot of detail here, but in between the two phases you’ll meet the nemesis of every BBQ Pitmaster – the Stall. It basically happens at about 165F for most meats and basically, for an extended period of time, your meat will just sit there and do nothing at 165F. Wrapping your meat at this point will help speed up the process.

Pork Butt (5-7lb): About 5 hours, 3.5 hours in the smoke, 1.5 hours wrapped in foil on the grill. Wrap at about internal temp 165F, place it back on the grill for another and pull when internal temp is 190F – 205F

Brisket (6lb): About six hours. Wrap at 4 hr mark (roughly 165F), finish off for 2 hrs. Pull at 190F.

Turkey Breasts X 3 (1lb each): About 2.5 hours. No need to wrap in foil (i.e., “crutch”) while cooking, just pull them at 165F, wrap them up in foil with some butter and let them rest for 20 minutes.

Types of Wood to Use

BBQ wood falls into two categories: hard woods and fruit woods. My go-to combination is equal parts Pecan (a hard wood) and Apple wood (a fruit wood), but I also use oak, hickory, cherry, peach and mesquite. Here’s a basic run-down on some basic types of wood and how to use them, organized from strongest to weakest flavor:

Mesquite (hardwood). Hot temperature, fast burn time. The mother of all hard woods, mesquite has a strong, earthy, leathery flavor. It’s really only useful for very short cooks (less than 30 minutes). Nothing can ruin a piece of meat quicker than too much mesquite. However, it’s quite good on lamb, burgers and roasted green chiles and other veggies. It quickly overpowers poultry, pork, and fish.

Hickory (hardwood). Hot temperature, long burn-time. The most commonly used hardwood, it’s pretty safe to use on anything other than fish. Be warned: It makes everything taste like bacon (which is either good or bad, depending on how you look at it).

Oak (hardwood). Hot temperature, medium burn time. Not as strong as hickory, and slightly sweeter. Safe for use on anything except fish. Good for slightly longer cooks as it’s flavor is more mild. Post Oak is the go-to in Texas BBQ, and for Santa Maria BBQ the go-to is Red Oak. White Oak is the mildest and is slightly reminiscent of Pecan.

Pecan (hardwood). Medium temperature, medium burn time. Mild, sweet and yet strong enough to stand up to even the gamiest of meats. Great on anything. Imparts a slightly nutty flavor. If I had to use only one wood for the rest of my life, this would be it.

Cherry (fruitwood). Medium temperature, long burn time. The strongest of the fruitwoods, it penetrates meat fairly quickly and imparts a rich, earthy flavor. It also tends to turn meat dark pretty quickly. Good on poultry and fish, and as a mixer with another hardwood. In my opinion, it makes beef too sweet.

Apple (fruitwood). Medium temperature, medium burn time. My go-to fruitwood. It takes a long time for it to penetrate meat, so it works well in combination with another hardwood. That being said, it’s awesome on fish by itself.

Peach (fruitwood). Low temperature, long burn time. Probably the mildest of the fruitwoods, peach is good for cold smoking fish and cheese, but not much else, in my opinion.

Note: Never, ever use pine or anything coniferous – the resin will ruin your grill and impart a nasty, acrid taste to everything. The one exception to this is if you’ve got some cedar planks that you have soaked for a while, they can be used to make some damned fine salmon – but that’s a whole other technique on a whole other post.

Happy Smoking!

The Intrepid Gourmet